It’s Not the Welfare State That’s Failing – It’s Capitalism

Why the debate about welfare benefits misses the real problem

The German social debate has a perception problem. Anyone following the political discourse might think that the greatest threat to our prosperity is people receiving welfare benefits. Not the tax evasion of billionaires. Not speculation on financial markets. Not the systematic redistribution from bottom to top over four decades. No: the problem is supposedly people who have to get by on 563 euros per month.

This diagnosis is not just wrong. It’s dangerously wrong. Because it distracts from the actual systemic failure – and thereby prevents any real solution.

The Great Confusion: Who’s Actually Failing Here?

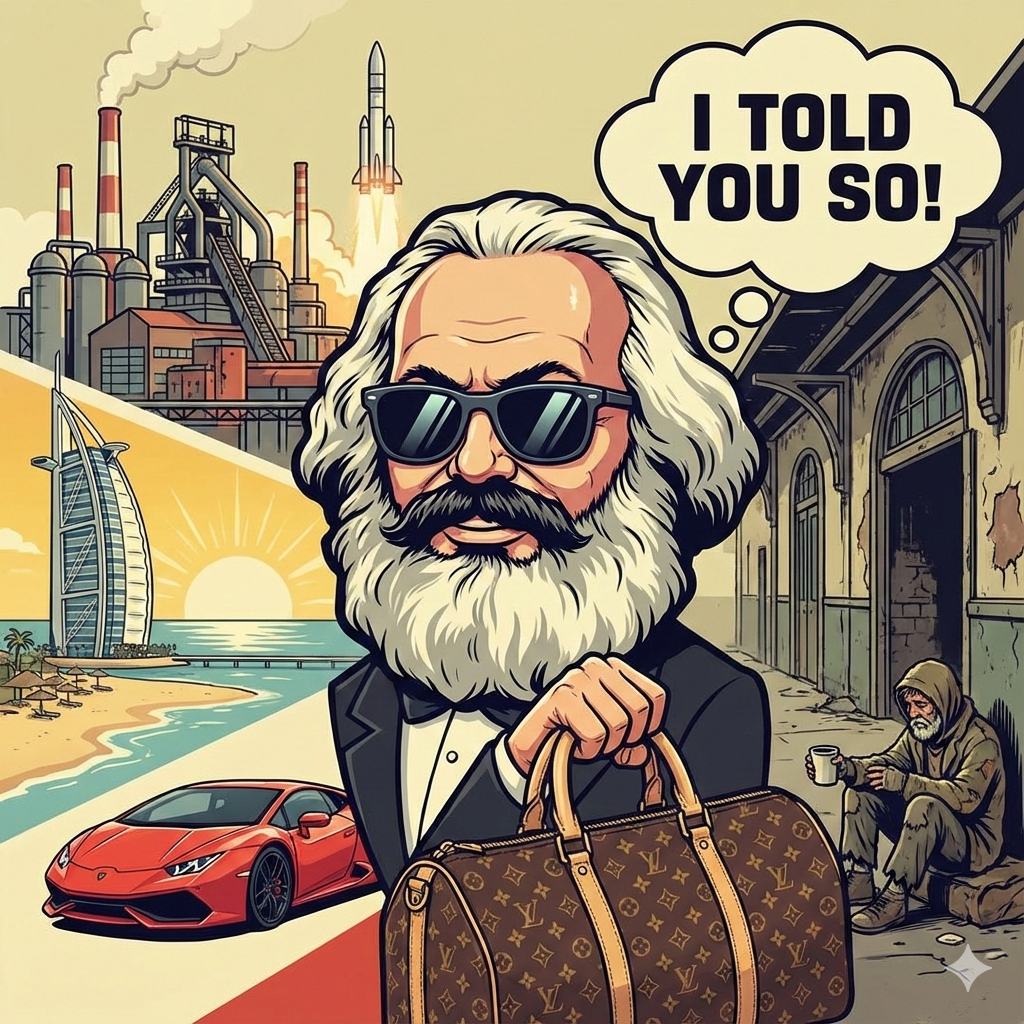

Political scientist Christoph Butterwegge puts it succinctly in his recent article in Der Spiegel: “It’s not the welfare state that’s failing, but capitalism.”[1] What at first glance seems like polemical exaggeration is, upon closer examination, a sober description of what has been happening for decades.

The logic of welfare state critics works like this: The state can only distribute what the economy has previously generated. When the economy weakens, the welfare state must shrink. Sounds plausible. But it’s a reversal of cause and effect.

The question is not whether we can “afford” the welfare state. The question is why a system that produces more wealth than ever before distributes this wealth ever more unequally. Why productivity gains no longer reach those who generate them. Why wages stagnate while profits explode.

The answer lies not in the welfare state. It lies in capitalism, which has fundamentally transformed since the 1980s.

What the Numbers Actually Show

Germany’s seventh Poverty and Wealth Report[2] makes clear: Poverty is a mass phenomenon in Germany. Not because the welfare state is too generous – but because it can only partially compensate for the massively grown inequality of market incomes.

Butterwegge cites a crucial number: The share of basic income support spending in the federal budget fell from 14 percent in 2014 to 10 percent in 2024. Not risen. Fallen. There can be no talk of “excessive growth of the welfare state.”

The Eurofound analysis for the EU concludes that the welfare state reduces market income inequality by approximately 42 percent on average.[3] Put differently: Without the welfare state, income inequality would be almost twice as high as it already is. The welfare state is not the problem. It’s the only thing keeping an even bigger problem somewhat in check.

The Historical Perspective: From Black Friday to the Financial Crisis

Anyone who wants to understand why welfare states emerged must understand the history of crises that made them necessary.

The Stock Market Crash of 1929

The “Black Friday” of 1929 was not simply a stock market event. It was the result of extreme wealth concentration in the “Roaring Twenties,” combined with speculative excesses and completely inadequate social security. When the bubble burst, there was no safety net. The consequence: a global depression, mass unemployment, political radicalization.

The lesson led to the construction of modern welfare states. In the USA, the New Deal; in Europe after World War II, the expansion of the welfare state. Not out of charity – but from the bitter realization that a society without a social safety net collapses in crisis.

The 2008 Financial Crisis

Eighty years later, the pattern repeated. Again extreme wealth concentration, again speculative excesses, again a crash. But this time with one crucial difference: The welfare states were still intact enough to prevent the worst collapse.

Macroeconomic studies quantify the “automatic stabilizer” effect of European social protection systems: They cushioned approximately 38 percent of proportional income shocks and 47 percent of idiosyncratic unemployment shocks.[4] The welfare state prevented a financial crisis from becoming a depression.

Ironically, governments rescued banks with hundreds of billions – and then began cutting social benefits to reduce the resulting debt. The perpetrators were rewarded, the victims burdened. Occupy Wall Street was the response: the protest against a system that privatizes profits and socializes losses.

The Transatlantic Comparison: What Happens When the Welfare State Shrinks

The USA is the great experiment in what happens when you systematically dismantle the welfare state. The result is clear – and sobering.

A 2020 RAND study quantifies the wealth transfer from the lower and middle classes to the upper class since 1975 at approximately 50 trillion dollars.[5] Fifty trillion. That’s not a typo. It’s the largest redistribution in human history – and it went from bottom to top.

The Economic Policy Institute has documented the mechanics of this redistribution.[6] From 1948 to 1979, productivity and wages in the USA rose in lockstep: Productivity grew by 108 percent, wages by 93 percent. This was no coincidence – it was the result of deliberate policy decisions that distributed growth broadly.

Then came the break. From 1979 to 2019, productivity grew by another 60 percent – but a typical worker’s wages grew by only 16 percent. Productivity and wages have decoupled. The surplus value that workers generate no longer flows back to them. It flows to the owners.

Had wage growth continued to track productivity, the median worker would earn $9 more per hour today. That’s over $18,000 per year for full-time work – per person. This is not abstract market failure. This is systematic expropriation through policy changes: deregulation, union-busting, erosion of the minimum wage, tax cuts for top earners.

Real wages for the lower and middle classes stagnated. Life expectancy is declining in certain population groups. Social mobility – the promise that anyone can make it – is now lower in the USA than in most European countries. That’s why “We are the 99%” didn’t come from a university seminar, but from the street.

Europe is doing better. But the trend is moving in the same direction. Since the neoliberal reforms of the 1980s and 1990s, inequality has been growing here too. The wage share is falling while capital returns are rising.[7] The difference: European welfare states have cushioned the fall so far. The question is, for how long – if they’re systematically dismantled.

Excursus: The Myth of European Decline

Speaking of Europe: Right now it’s important to correct a widespread misconception. The US government claims in its current security strategy that Europe is in economic decline.[8] Elon Musk and Jamie Dimon, the CEO of JP Morgan, echo this. The narrative of the lagging continent is popular – and it’s a myth.

French economist Gabriel Zucman has examined the numbers more closely.[9] His finding: “The claim that the EU is far behind the USA is simply false.” Since 1990, GDP per capita has grown by 70 percent in the USA and by 63 percent in the EU-27. That corresponds to average annual growth of 1.6 percent in the USA and 1.5 percent in the EU. Not a huge difference.

Yes, the level of GDP per capita is 35 to 40 percent higher in the USA than in the EU. But according to Zucman, this gap is explained “predominantly by the fact that people in the EU work fewer hours – not because Europeans are less productive.”

What matters is productivity per hour worked. According to data from the World Inequality Database, it stands at 60 euros per hour in the USA – exactly equal to the EU core countries Germany, France, Italy, Spain, Netherlands, and Belgium. Northern Europe is even above the US level. Statistics from the International Labour Organization (ILO) confirm this: GDP per hour worked is $81.80 in the USA, $83 in Western Europe.

Additionally, the USA generates its GDP at significantly higher ecological costs – CO₂ emissions per hour of production are significantly lower in the EU.

Zucman’s conclusion: “More leisure time, better health outcomes, less inequality, fewer CO₂ emissions, and all this with largely similar productivity: The EU can be proud of its development model, and the Trumpists should tone it down – as should the European conservatives who parrot them.”

A comprehensive study by the Hans-Böckler Foundation comparing 80 indicators confirms this finding.[10] Germany performs better than the USA in 10 of 15 examined areas. Life expectancy: 81 years in Germany, 76 in the USA – despite the USA spending 16.6 percent of GDP on healthcare, Germany only 12.7 percent. Homicide rates per 100,000 inhabitants are eight times higher in the USA.

The median American – the person exactly in the middle of the income distribution – doesn’t live significantly better than the median European. They just work more, have less security, and die earlier. The European welfare state produces fewer billionaires – but also fewer homeless people, fewer uninsured, fewer working poor. That’s not failure. That’s a deliberate choice for a different economic model.

What Research Says: Inequality Harms Growth

There’s a persistent narrative: Redistribution harms growth. Tax the rich and you take away their incentive to invest. Support the poor and you take away their incentive to work. The argument sounds intuitively plausible. It’s just empirically wrong.

The International Monetary Fund – not exactly a left-wing organization – concludes in several studies that high income inequality is associated with weaker and less stable growth.[11] Redistribution through taxes and transfers does not, on average, slow growth – and can even promote it through reduced inequality.

OECD analyses confirm this finding: Increasing inequality weakens long-term growth.[12] The mechanism is understandable: When a growing portion of the population has no opportunities for advancement, they invest less in education. When the middle class shrinks, so does purchasing power. When wealth concentrates, productive investment declines in favor of speculative assets.

A LUISS study of the EU-27 shows: Higher spending on health, education, and social security correlates with better indicators of economic prosperity.[13] The welfare state is not a burden on the economy. It’s a prerequisite for it.

The Welfare State as Economic Stabilizer

Butterwegge makes a point that’s often overlooked in the debate: A strong welfare state doesn’t just stabilize society – it stabilizes the economy.

The logic is simple: When welfare benefits decline, over 500,000 single parents and millions of other people have less money to spend. This doesn’t just affect them. It affects retail, which sells less. The consumer goods industry. Overall domestic demand.

A euro that goes to a welfare recipient is spent almost 100 percent – and in local retail, at the bakery, at the discount store. A euro in tax relief for a billionaire might flow to an account in the Cayman Islands. “Austerity measures” on social benefits save in the wrong place. They cost growth instead of promoting it.

For Skeptics: Why Wealth Taxation Makes Economic Sense

For those who still believe that taxing the rich is just envy politics: Here’s the summary in numbers.

Fact 1: Germany’s wealth tax was suspended in 1997. Since then, the wealth of the richest Germans has grown by several hundred percent. The wages of the majority have barely risen in real terms. That’s no coincidence – it’s the result of political decisions.

Fact 2: Thomas Piketty has empirically demonstrated that the return on capital is higher than economic growth in the long run.[14] This means: Those who already have wealth automatically get richer – faster than the economy grows. Without correction through taxation, this inevitably leads to ever more extreme concentration.

Fact 3: The IMF – again: not a left-wing party – recommends stronger taxation of high wealth and income as a means against inequality, without harming growth.[15]

The simple truth: A billionaire who pays ten percent more in taxes doesn’t change their lifestyle. A welfare recipient who receives five percent less must decide whether to buy heating or food. The “high achiever debate” has lost sight of who actually bears the burden in this country.

Those who want to create prosperity must distribute it. Not out of pity – but because concentrated wealth is economically inefficient. It sits in accounts instead of circulating. It flows into speculation instead of productive investment. It buys a third vacation home instead of generating domestic demand.

What’s Really at Stake

Butterwegge warns that the rigid harshness in social and refugee policy corresponds to the “increasing brutalization of the educated and propertied classes.” This is not an exaggeration.

When a virologist like Hendrik Streeck publicly questions the medical care of elderly people, we’ve reached a point where the basic norms of the German constitution – human dignity, the social state principle – are no longer taken for granted. Articles 1 and 20 of the Basic Law have an eternity clause. Not because they’re nice. But because the generation that wrote the Basic Law knew what happens when they’re abandoned.

Butterwegge quotes Bismarck – and that’s no coincidence. Even the conservative Chancellor understood that a welfare state is not charity but a necessity. He introduced social insurance to preserve social peace. Today, some want to transform this system back into a “charity, alms, and soup kitchen state.”

Conclusion: Shame Must Change Sides

What Germany needs is not the dismantling of the welfare state. It’s a restructuring of the economic system that puts it under pressure.

Butterwegge demands: “Social shame must change sides – from the poor, who often don’t even claim the support they’re entitled to, to the causes of poverty.” This includes employers who pay starvation wages. Property owners who engage in rent gouging. And yes – also politicians who want to implement “painful reforms,” meaning cut social benefits, while waving through tax gifts for the wealthy.

Capitalism has failed – not by its own standards (profits are still being generated), but by the standards of a democratic society. Growth that benefits only a small minority is not progress. It’s regression with better PR.

The welfare state is not a burden. It’s the foundation on which everything else stands. Those who dismantle it destroy not only the social safety net – they also destroy the basis for economic stability, social cohesion, and democratic legitimacy.

It’s time to turn the debate on its head.

Appendix: Three Sentences Even the Board of Directors Will Understand

For those who prefer thinking in balance sheets rather than morals – here’s the summary in CFO language:

- The welfare state is infrastructure. Without security there’s no mobility, without mobility no efficient labor allocation, without efficient allocation less productivity. Unemployment, illness, care needs, old age – these aren’t marginal risks but predictable life realities. The welfare state turns them into collective insurance instead of individual catastrophe. And insurance has a property that markets love: it reduces uncertainty. Less uncertainty means more investment, more mobility, more startups.

- Inequality is a risk indicator. It lowers long-term potential growth, increases political risks, and makes crises more expensive. The IMF and OECD don’t say this for fun. When the economy turns down, transfers and progressive taxes stabilize income and consumption – a built-in shock absorber. Whoever calls for “less welfare state” is effectively calling for more volatility.

- Wealth taxation is risk management. If you don’t collect the costs of stability from wealth, you’ll get them back later through crises, bailouts, radicalization, and location flight – just more expensive, more chaotic, and more politically destructive. 2008 showed that instability in the financial system produces gigantic follow-on costs. Stronger taxation of very large fortunes is – in business terms – an insurance premium.

Why Wealth Must Be Taxed – A Conservative Perspective

The question is not: Do we want to take something from the rich? The question is: Do we want to preserve a market economy that functions without political and social erosion?

Wealth is power. Very high wealth isn’t just “saved income.” It’s a structural resource of influence over markets, media, politics, real estate, prices. When wealth becomes highly concentrated, rentier logic emerges: returns from ownership replace returns from performance. Translated for conservatives: That’s bad for competition. Bad for small business. Bad for the idea that markets reward performance.

Taxing wealth relieves labor. Germany taxes labor and consumption heavily, wealth comparatively lightly. If you want to finance the welfare state without further burdening the middle, the tax base must be broadened. This isn’t a class issue. It’s a structural issue: If you always put the load on the same beams, don’t be surprised about cracks.

Property is not a state of nature. It’s a legal construct. It exists because the state and institutions guarantee it: police, courts, land registry, contracts, currency, infrastructure, education system, political peace – that’s the platform on which wealth can grow safely. Wealth taxation is therefore not a punishment but a usage fee for system stability. Or simpler: Whoever benefits most from the stable operating system can also make the largest contribution to its maintenance.

Without social legitimacy, property becomes politically risky. Property in a democracy is guaranteed by the consent of the majority that this system is fair enough. When this consent erodes, you don’t get “better markets” but populist expropriation fantasies, scapegoat politics, institutional coarsening. A well-designed wealth tax is, from a conservative perspective, not an attack on property – but an insurance policy for property.

The Three Standard Objections – Taken Seriously

“Wealth tax is double taxation.” Partly – but the argument is flawed because it pretends that wealth is just “income in a piggy bank.” In reality, very high wealth often consists of company shares, real estate values, capital gains, monopoly rents – that is, increases in value that are not identical to already fully taxed labor income. Besides: VAT also taxes money that was already taxed as income. The system doesn’t live by a purity principle but by fairness and ability to pay.

“That drives capital away.” Capital is mobile – yes. But that’s a design problem, not a killer argument. High exemptions, deferral and liquidity rules for business assets, exit tax mechanisms, international cooperation: These are tools, not utopia. Countries are already organizing global minimum standards for corporate taxes – why should wealth be sacrosanct? Those who claim it can’t be done are often really saying: “I don’t want to.”

“Valuation is too complicated.” Complicated, yes. Impossible, no. Germany already values real estate and wealth in many contexts – inheritance, property tax, accounting. The question is political priority, not technical magic. The fact that the wealth tax has not been levied in Germany since 1997 had to do with valuation and equality issues – not with wealth taxation being constitutionally “prohibited.”

The Uncomfortably Simple Calculation

Capitalism rarely fails due to lack of efficiency. It fails because, without corrections, it’s too good at producing winners – until the winners become so large that the market becomes a facade.

And when you say “wealth tax,” many hear “punishment.” They should hear “maintenance contribution”: for stability, competition, legitimacy – and for the simple truth that a society cannot simultaneously have maximum wealth concentration and maximum democratic tranquility.

Wealth taxation is not an attack on achievement. It’s an investment in the conditions under which achievement matters again.

Sources

Complete source references can be found in the footnotes. Key studies:

- IMF Staff Discussion Note 14/02: Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth

- OECD (2015): In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All

- OECD (2015): All on Board: Making Inclusive Growth Happen

- Eurofound (2023): Developments in Income Inequality and the Middle Class

- RAND Corporation (2020): Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018

- LUISS LEAP Working Paper (2024): Welfare Spending and Cross-Country Economic Disparities

- Piketty, T. (2014): Capital in the Twenty-First Century

- Butterwegge, C. (2025): Der Spiegel 49/2025

- Economic Policy Institute (2020): The Productivity-Pay Gap

- Hans-Böckler Foundation / Priewe (2024): Working and Living Conditions in Germany and the USA

- Frankfurter Rundschau / Zucman (2024): Europe is more productive than claimed

[1]Butterwegge, Christoph (2025): Der Sozialstaat? Von wegen, der Kapitalismus hat versagt. Der Spiegel 49/2025.

[2]Federal Government of Germany (2025): 7th Poverty and Wealth Report (7. Armuts- und Reichtumsbericht).

[3]Eurofound (2023): Developments in Income Inequality and the Role of the Middle Class. The welfare state reduces market income inequality by approximately 42%.

[4]McKay, Alisdair & Reis, Ricardo (2016): The Role of Automatic Stabilizers in the U.S. Business Cycle. Econometrica 84(1), 141-194.

[5]RAND Corporation (2020): Trends in Income From 1975 to 2018. Approximately $50 trillion transferred from the bottom 90% to the top.

[6]Economic Policy Institute (2020): Growing inequalities have generated a productivity-pay gap since 1979. Productivity has grown 3.5 times as much as pay for the typical worker.

[7]IMF World Economic Outlook: Globalization of Labor. Analysis of declining labor share and rising capital returns.

[8]National Security Strategy of the United States (2024): Claims of European economic decline.

[9]Frankfurter Rundschau / Stephan Kaufmann (26.12.2024): Based on Gabriel Zucman’s analysis of EU vs. US productivity.

[10]Priewe, Jan (2024): Working and Living Conditions in Germany and the USA. Hans-Boeckler Foundation. 80 indicators compared.

[11]IMF Staff Discussion Note 14/02 (Ostry et al. 2014): Redistribution, Inequality, and Growth.

[12]OECD (2015): In It Together: Why Less Inequality Benefits All.

[13]LUISS LEAP Working Paper (2024): Welfare Spending and Cross-Country Economic Disparities in the EU-27.

[14]Piketty, Thomas (2014): Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Harvard University Press.

[15]IMF Fiscal Monitor (2017): Tackling Inequality.